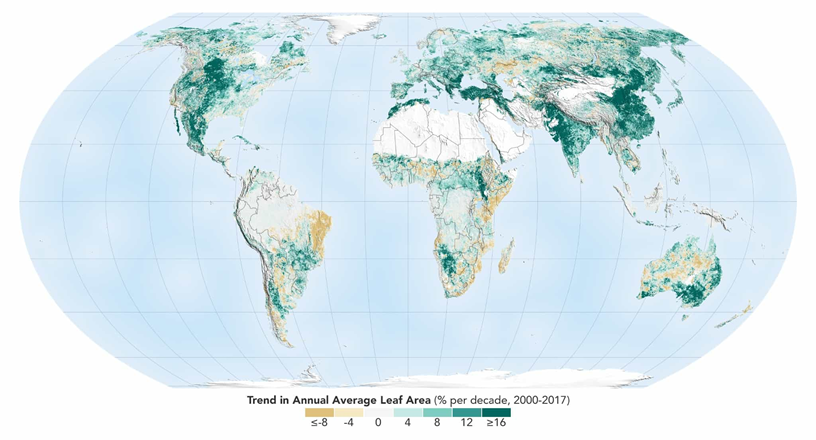

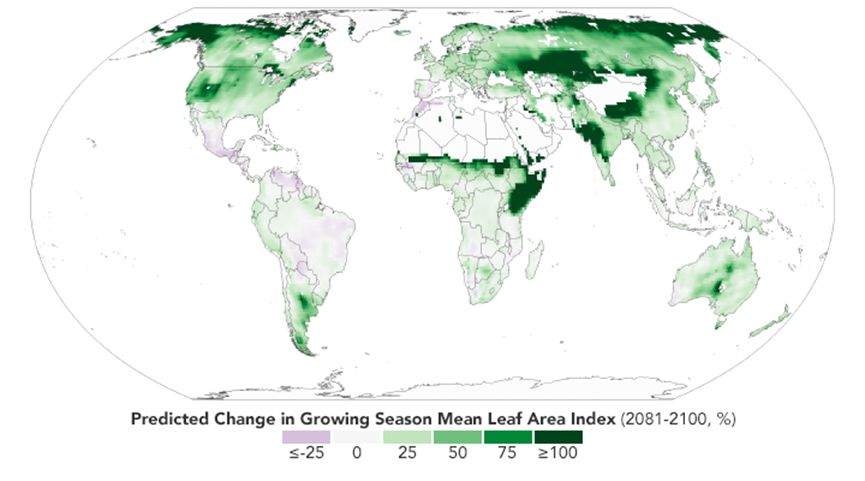

According to satellite data from NASA Earth Observatory, the earth is becoming greener in the past 20 years, with an increase in leaf area on plants and trees equivalent to the area covered by all the Amazon rainforests.

Nonetheless, greening up may not always be a good thing.

The Arctic, where sees ice and snow most of the year, is greening up. According to Rama Nemani of NASA’s Ames Research Center, Svalbard in the high-Arctic has seen a 30 percent increase in greenness.

Some theories suggest that this “Arctic greening” will help counteract climate change. The idea is that since plants take up carbon dioxide as they grow, rising temperatures will mean Arctic vegetation will absorb more carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, ultimately reducing the greenhouse gases that are warming the planet.

But is it the truth?

Donatella Zona, an associate professor of biology at San Diego State University, and her team studied carbon sequestration of Arctic plants.

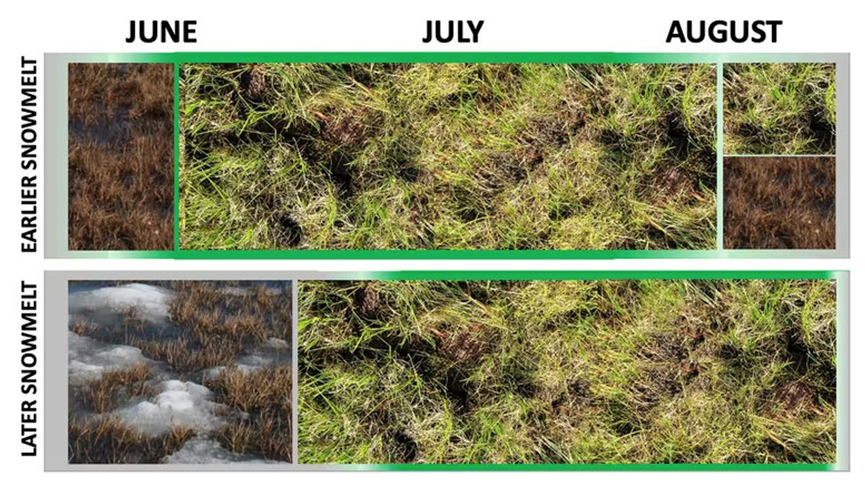

The research showed a surprising result. Although the rising temperature lengthens Arctic plants’ growing season, plant productivity and carbon sequestration decline in the late season. The Arctic becoming greener does not increase carbon sequestration.

Moreover, Arctic greening has another problem.

Normally, plants on the tundra store more carbon through photosynthesis than the tundra releases, making it a vast carbon sink. The long, cold winters slow plants’ decomposition and lock them in the frozen ground. However, when permafrost holding this and other organic matter thaws, it releases more greenhouse gases into the atmosphere.

Therefore, the growing plants in the Arctic region cannot reduce the amount of carbon dioxide in the air. The thawing permafrost would only worsen the situation. The area would lose carbon sink and release carbon dioxide into the air.

Humans should not expect Arctic vegetation to help alleviate global warming. To save the climate, we need to keep working on carbon reduction activities.